Introduction

Ed Ruscha is widely regarded as one of the world’s most important artists with a career spanning six decades from the early 1960s until the present day. Through key works from the ARTIST ROOMS collection discover the art and ideas of this extraordinary artist.

Ruscha became well known in the late 1950s when he began making small collages using images and words taken from everyday sources such as advertisements. This interest in the everyday led to him using the cityscape of his adopted hometown Los Angeles – a source of inspiration he has returned to again and again. Ruscha often combines images of the city with words and phrases from everyday language to communicate a particular urban experience. He also explores the banality of modern urban life and the barrage of mass media-fed images and information that confronts us daily.

Ruscha, pop, and conceptual art

Ed Ruscha's use of the imagery and techniques seen in commercial art such as advertising and his interest in popular culture and the everyday, connects him directly with pop art.

He was also very influential to the development of conceptual art through his depiction of words and phrases, and his books of deadpan photographs characterised by their low-key humour.

Words and phrases

Edward Ruscha

HONK (1962)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

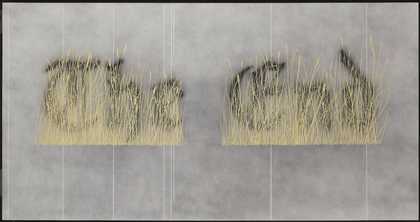

Edward Ruscha

The End #1 (1993)

Tate

I’m dead serious about being nonsensical.

Ed Ruscha

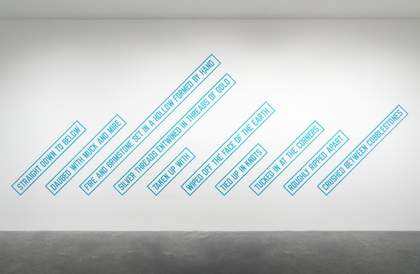

Words and phrases are at the centre of Ed Ruscha’s work and first appear in his paintings as early as 1959. The use of words and text in twentieth century art can first be traced back to cubist painters such as Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso who added letters and words, painted and collaged, into still lifes. Playing with language was also central to dada artists who left an important legacy with their radical, often humorous use of words. The dadaists were an early influence on Ruscha and his use of words in an ambiguous and playful way could be seen as an expression of that influence.

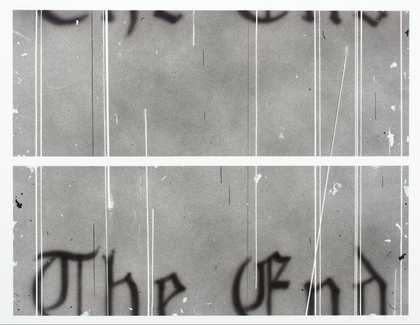

Ruscha plays with language in his text pieces, using devices such as onomatopoeia (a word that sounds like its meaning), puns, alliteration (a phrase or series of words where the first or second letter is repeated), and contrasting meanings. Many of his early works such as Honk 1962 depict single words in a strong typographic format or font. A more brooding atmosphere emerges in the later series, The End, which illustrates the words overlaid with imagery recalling fading film credits. Other works such as Pay Nothing Until April 2003 reference advertising while setting the text against a mountainous landscape.

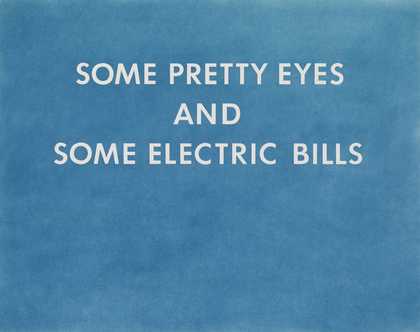

Ruscha’s group of ‘catch-phrase’ drawings dating from the 1970s, including Pretty Eyes, Electric Bills 1976, mix visual formality with playful language. In this series of pastel drawings Ruscha set his pithy phrases against fields of colour.

Edward Ruscha

PRETTY EYES, ELECTRIC BILLS (1976)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

The sentences and phrases suggest everyday American language and slang, and draw attention to a particular experience or recall the excesses of Hollywood culture. In Pretty Eyes, Electric Bills 1976, the juxtaposition of the phrases ‘PRETTY EYES ’ and ‘ELECTRIC BILLS’ is at odds; the first conjures romantic and evocative images while the second makes reference to a mundane chore. This is how Ruscha explains his drawing:

Pretty Eyes, Electric Bills is my way of separating two subjects that are on the far end of the world from each other. This somehow gets to be the reason that I want to make a work of art of this discord.

What do you think? Words, sounds and meanings

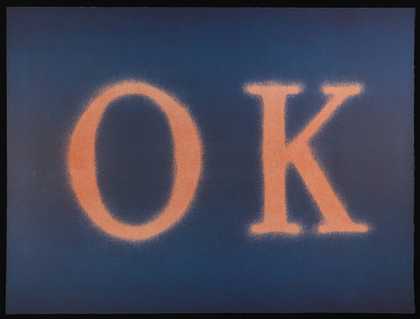

Edward Ruscha

OK (State I) (1990)

ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by Artist Rooms Foundation 2011

Identify words or phrases that you like and think about whether they are specific to the way you speak. Why do you like them? Is it the shape of the individual letters, the way they sound, or the meaning of the words?

Literature

I read what I want to read. I think most people do that. Or I read what I want to see.

Ed Ruscha

The words Ed Ruscha uses in his work come from a variety of sources including books which occasionally suggest images to him:

I’ve done a few paintings using verbatim words from certain sections of books. Of course the words I use come from every source. Sometimes they happen on the radio and sometimes in conversations. I’ve had ideas come to me literally in my sleep and I tend to believe on blind faith, that I feel obliged to use.

Ruscha is an admirer of the British writer J.G. Ballard and the American writers Don DeLillo and Tom McGuane. He has said that Ballard ‘cuts open the belly of what’s going on and everything falls out.’ Ballard’s fiction is associated with dystopian modernity (an idea of modernity or the future where everything is unpleasant or bad). He writes about bleak man-made landscapes and the psychological effects of technological, social or environmental developments.

In his painting The Music from the Balconies 1984 Ruscha uses text from J.G. Ballard’s novel High Rise 1975. The novel, set in a high rise, is the tale of urban disillusionment. Society slips into a violence as the isolated inhabitants of the high-rise, driven by primal urges, recreate a frightening world ruled by the laws of the jungle. In The Music from the Balconies Ruscha juxtaposes a beautiful landscape and serene skyline layered with the dark and unsettling quote 'The Music from the Balconies Nearby Was Overlaid by the Noise of Sporadic Acts of Violence'. This pairing seems itself an act of violence, overlying the tranquil landscape with the wordy Ballard quote.

Books and photographs

I’m not interested in books as such but I’am interested in unusual publications. The first book came out of a play on words. The title came before I even thought of the pictures. I like the word 'gasoline' and I like the specific quality of 'twenty-six'.

Ed Ruscha

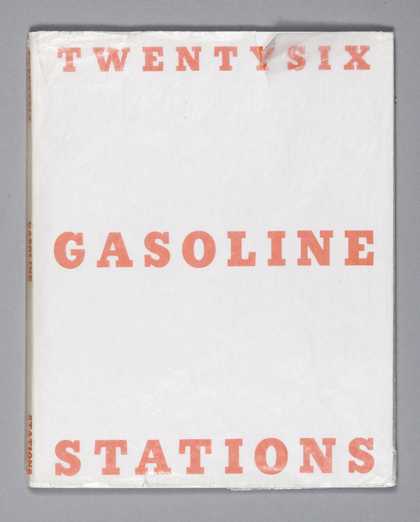

Edward Ruscha, Twentysix Gasoline Stations, 1963

© Ed Ruscha

Ed Ruscha’s first book Twentysix Gasoline Stations 1962 featured photographs he took as he travelled along Route 66, between Los Angeles and his parents’ home in Oklahoma City, taking in Arizona, New Mexico and Texas. The pictures, which have no people in them, do not document a particular journey and there is no sense of narrative or story. Twenty Six Gasoline Stations was the first of seventeen books that Ruscha made throughout the 1960s and 70s. These books are characterised by their use of serial photography, a wry sense of humour and use of small amounts of text. The titles of the books such as Every Building on Sunset Strip 1966 and Thirtyfour Parking Lots 1967 function as banal descriptions of the subject matter.

The artist talks about the 'cultural curiosities' which fill his photography book series

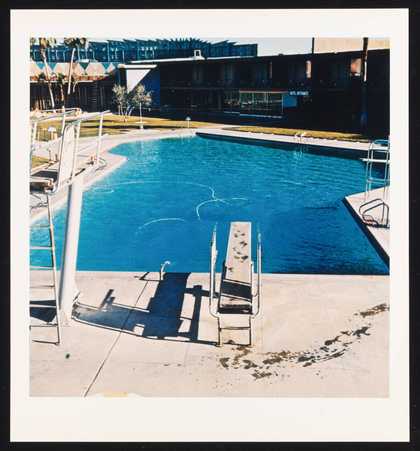

Edward Ruscha

Pool #5 (1968, printed 1997)

ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by Artist Rooms Foundation 2011

The photographs in Ruscha’s books are black and white until Nine Swimming Pools (and A Broken Glass) 1968 when he introduces colour. This book featured nine photographs of pools from a selection of hotels in LA and Las Vegas followed by a sequence of black pages. Again, for the most part, these photographs have no people in them, so they feel deserted and vacant. However a suggestion of human presence is referenced in Pool #5 1968/97 where liquid footprints lead up to the diving board.

Ruscha’s books were very influential in the conceptual art movement. As with conceptual art generally, with the books it is the idea behind them that is important – and it is this that dictates what they look like. An interest in structure, serial imagery and the mundane are also characteristic of conceptual art.

Hollywood

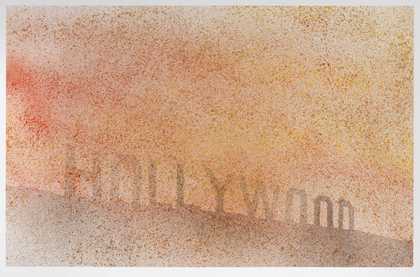

Edward Ruscha

DEC. 30th (2005)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

I looked outside my window here and I saw the sign ‘Hollywood’ and it became the subject matter for me.

Ed Ruscha

Ed Ruscha has lived and worked in Los Angeles since 1956. The city and its film industry have been a huge influence on Ruscha and the visual language he uses.

The word ‘Hollywood’ and symbols such as the Twentieth Century Fox logo appeared in Ruscha’s work from the 1960s. The dimensions of Dec. 30th 2005 call to mind the format of widescreen movies. In this painting, the Hollywood sign, an iconic feature of the Los Angeles skyline, is silhouetted and blurred with orange and red spray paint. The colours and the shaded sign suggest a sunset or blazing white heat. Ruscha has exploited the sign as a monument to the town’s myths and dreams in his work since the late 1960s.

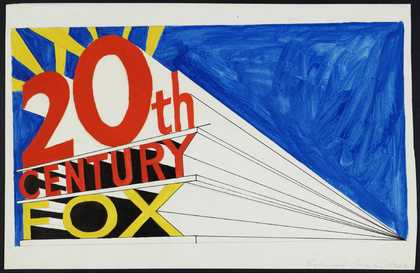

Edward Ruscha

Trademark #5 (1962)

Tate

As well as directly referencing the signs and symbols of Hollywood's film industry, the look and process of filmmaking – and the cinema experience – have also inspired Ruscha's images and techniques.

In paintings such as Pay Nothing Until April 2003, Ruscha's placement of words against a mountainous landscape suggest the opening credits in an action adventure film.

For his book Every Building on Sunset Strip 1966 Ruscha directly references the act of making a film. The photographs for this book were created by attaching a camera to a moving vehicle and shooting in real time.

A bright beam of light entering a black space in Miracle #64 1975 and similar works, reminds us of a film being projected in a cinema.

‘Hollywood dreams’ – I mean, think about it. Close your eyes and what does it mean, visually? It means a ray of light, actually, to me, rather than a success story.

Ed Ruscha

Edward Ruscha

Miracle #64 (1975)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Movies are also referenced in The End series, which illustrate the words with imagery that recalls fading film credits (The End #40 2003). Works such as Miracle #64 and The Final End 1992 seem to present Hollywood success as a near religious experience.

Edward Ruscha

The Final End (1992)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Have a go: Film into art

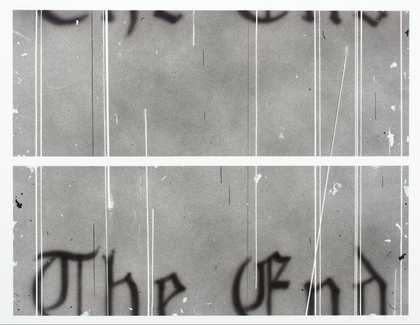

Edward Ruscha

The End #1 (1993)

Tate

Use some of the key words or a catchphrase from the credits, poster or trailer of your favourite movie to create an artwork. Think about what the film might be like or whether or not you want to create a visual representation of the film.

Materials

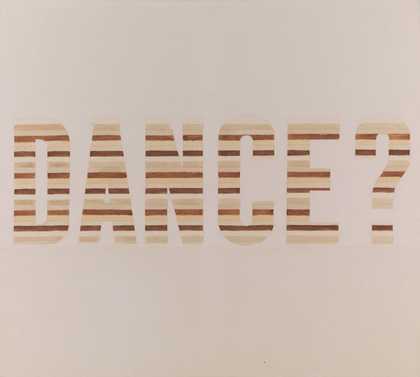

Edward Ruscha

DANCE? (1973)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

The first work that I did involving vegetable matter and organic materials came out of a frustration with materials. I wanted to expand my ideas about materials and the values they have.

Ed Ruscha

It is the physical quality of art materials such as paper and ink that sparked Ed Ruscha’s interest in art. As a boy he discovered art through the medium of Higgins India ink through a friend who was using the ink in his cartoons: ‘I had a very tactile sensation for that ink; it’s one of the strongest that has affected me as far as my interest in art.’ This fascination with the tools of the artist’s trade continued throughout his career.

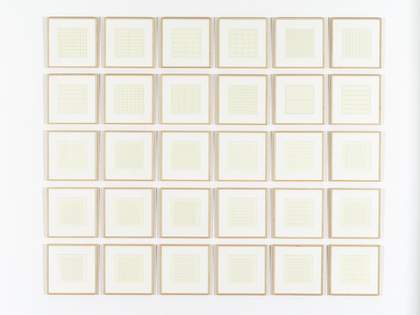

In the late 1960s Ed Ruscha experimented with more unusual materials. The print portfolio Stains 1969 consists of seventy-five works on paper made using egg yolk, turpentine, beer, salad dressing and gunpowder. Inside the portfolio case, which contains the series of prints, was one final stain: the blood of the artist.

Ruscha’s experimentation with materials continued into the 1970s. DANCE? 1973 was made using a range of materials including coffee, egg white, mustard, chilli sauce, ketchup and cheddar cheese. As well as reflecting Ruscha’s interest in unusual materials it also highlights his fascination with symbols of American popular culture of the 1960s and 1970s. The invitation to dance suggests light-hearted entertainment, while the edible materials are the kind of foodstuffs that might be consumed in an American diner as an accompaniment to hamburgers or hotdogs.

Everyday

Edward Ruscha

Vacant Lot #1 (Anaheim) (1970, printed 2003)

ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by Artist Rooms Foundation 2011

Edward Ruscha

Vacant Lot #2 (Van Nuys) (1970, printed 2003)

ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by Artist Rooms Foundation 2011

Edward Ruscha

Vacant Lot #3 (La Mirada) (1970, printed 2003)

ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by Artist Rooms Foundation 2011

Edward Ruscha

Vacant Lot #4 (Los Angeles) (1970, printed 2003)

ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by Artist Rooms Foundation 2011

The everyday or commonplace is the subject matter of many of Ed Ruscha’s paintings, photographs, books, prints and drawings. His black and white photographs and books depict banal and familiar subjects such as apartment blocks, car parks and palm trees. Gas stations, the Hollywood sign and trademarks populate his paintings. Speaking of his first book Twentysix Gasoline Stations 1962 Ed Ruscha once said that his photographs were merely a collection of facts and his books are is like ‘a collection of readymades.’

Artist Marcel Duchamp, invented the term readymade to describe his series of works in which ordinary found objects were transformed by presenting them in a gallery. Duchamp argued that art was about ideas and by choosing an everyday object he was making it into a work of art. Duchamp was a key influence on Ruscha and the emergence of conceptual art in the late 1960s. Artists grouped under this broad title increasingly questioned the nature of art, and the role and status of the artist.

For his book Real Estate Opportunities 1970 Ruscha made a series of photographs, intended to look like conventional real estate photographs, of empty lots captioned with the locations. Four photographs from the Real Estate Opportunities shooting sessions were later editioned in 2003 as Vacant Lots 1970/2003.

Have a go: Documenting the everyday

Edward Ruscha

Filthy McNasty’s (Sunset Strip Portfolio) (1976, printed 1995)

ARTIST ROOMS

Tate and National Galleries of Scotland. Lent by Artist Rooms Foundation 2011

Take photographs of places, which you encounter on a daily basis or are perhaps part of your daily routine. Think about how you might present them e.g. in a book form or a gallery wall.

Landscapes

It’s not a celebration of nature. I’m not trying to show beauty. It’s more like I’m painting ideas of ideas of mountains. The concept came to me as a logical extension of the landscapes that i’ve been painting for a while – horizontal landscapes, flatlands, the landscape I grew up in. Mountains like this were only ever a dream to me; they meant Canada or Colorado.Ed Ruscha

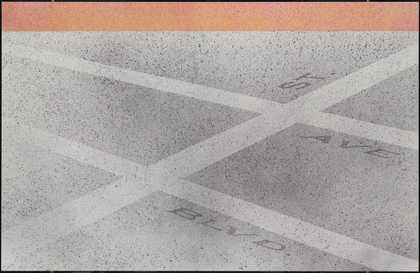

Ruscha continued to use images of landscapes in the work he made at the end of the twentieth century and beginning of the twenty-first. His metro plots are ariel views of metropolitan areas defined by intersecting parallel lines of the grid system or by actual written names of Los Angeles streets and avenues. These works such as BLVD.-AVE.-ST. 2006 bring together various concerns that have appeared in Ruscha’s work throughout the previous decades such as the photographic books of the 1960s that document subjects found along Los Angeles streets.

Edward Ruscha

BLVD.-AVE.-ST. (2006)

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Plotting, mapping, identifying and labelling are among the most prominent themes in Ruscha’s work. With the metro plot series Ruscha began to elaborate on the aerial perspective that he first introduced in his gasoline station paintings of 1962. Ruscha once said: ‘I guess I’ve always been intrigued by oblique perspectives, like ariel views. There’s something about the tabletop … taking a viewer up in the air, so you can look down from an angle.’

Around the same time as he began to make his metro plots Ruscha was also using found images unrelated to LA – bold and colourful mountain ranges. Some of these works superimposed words and phrases, such as 'Pay Nothing Until April’ and ‘Daily Planet’, over the mountain landscape. The phrases sound like advertising slogans or titles of newspapers or magazines. The text seems at odds with the landscape making the meaning of these works elusive or mysterious.